Why the first case with no animal link is worrying

Since April, the H5N1 avian influenza virus, also known as bird flu, has spread like wildfire in America.

The virus has been detected in wild birds, poultry, and dairy cows. Nearly 200 dairy herds in 14 states have tested positive for the H5 strain.

There have also been a handful of confirmed cases in dairy and poultry workers. On September 6, the 14th human case was confirmed. The case was detected in Missouri through the state’s seasonal flu surveillance system.

Unlike previous cases, the person had not been in close contact with infected dairy cattle or poultry. Nor were they exposed to raw milk – another source of the infection.

The individual tested positive after being hospitalised for other underlying health conditions and presented with symptoms such as chest pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and weakness. They were given antiviral medication and have since recovered, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

On September 13, the CDC shared new information about the case from Missouri officials, including that a household contact got sick with similar symptoms the same day and that a healthcare worker had mild symptoms.

More worrying still, the household member who developed symptoms on the same day as the patient was not tested for the flu.

The person had not been in close contact with infected dairy cattle or poultry. Nor were they exposed to raw millk

Getty Images

There’s a blood test to check for antibodies to H5N1 that may be done as soon as 10 days after infection, but antibody testing has not started, CDC officials said on Thursday.

The patient with a confirmed infection underwent extensive interviews on recent activities, such as doing yard work, having a bird feeder, keeping any pets at home, visiting agricultural fairs or petting zoos, eating undercooked meat, or drinking raw milk.

According to Nirav Shah, principal deputy director of the CDC, epidemiologists have not found a clear source of exposure.

“Missouri is working really hard to go deeper into the [epidemiology] to see if there are any unperceived exposures that are possible,” said Demetre Daskalakis, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

Genetic sequencing has revealed that the person had a rare mutation.

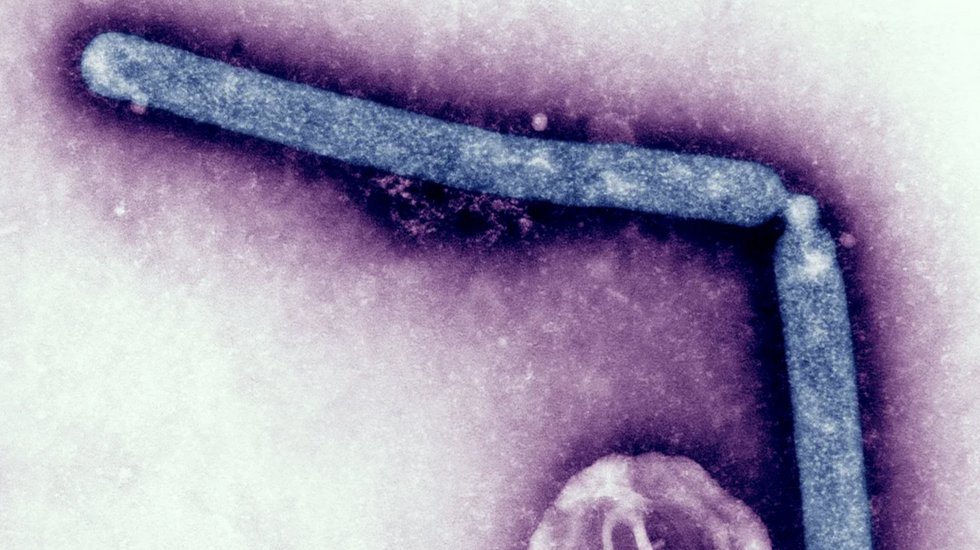

Due to low amounts of genetic material in the sample, the CDC has only been able to partially sequence the virus genome but its analysis revealed two mutations not seen in previous human cases, both of which occurred in a protein called hemagglutinin.

This protein is similar to the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 – the coronavirus that causes Covid-19 – in that it helps the virus bind to and infect cells. One of the mutations – A156T – has been identified in fewer than one per cent of samples collected from dairy cows.

The impetus to find a link to animals or raw milk is understandable.

Hanging over this case is the spectre of human-to-transmission. So far, there’s no evidence of that H5N1 has acquired this adaption but the development is making virologists nervous – and for good reason.

The mortality rate for H5N1 humans is high, with a 52 per cent case fatality rate (CFR) from January 1, 2003, to July 19, 2024.

However, this may be an overestimate as some people may have no symptoms or only mild symptoms.

How worrying is the Missouri case?

“This case definitely needs to be taken seriously,” Doctor Ed Hutchinson, Senior Lecturer, MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research, tell GB News.

He takes comfort in the knowledge that the individual has now recovered, which is in keeping with the previous cases.

“What makes this case different is that the other cases worked with dairy cattle and had clear routes of exposure to the virus. This patient does not have a known history of exposure to the virus. We don’t yet know how they became infected, and we need to know how they got infected to understand whether H5N1 is getting better at spreading in humans,” he said.

According to Doctor Hutchinson, there seem to be three possible options.

It could still be established that there was contact with an animal (a cow or something else) that we’re not yet aware of – this would make the case similar to the thirteen others that we know about where there was contact with cattle.

Contamination from raw unpasteurized (‘raw’) milk also cannot be ruled out. If so this could help public health officials to better direct efforts to contain the virus, notes the doc.

It is also possible that the patient contracted the virus from another infected person – though at the moment there is no evidence of this.

This would be a major red flag because spreading from person to person is the sort of thing that the virus needs to get good at in order to spread in humans, Doctor Hutchinson explained.

The spillover from cows to humans already suggests that HN51 is rapidly evolving in this direction.

As Doctor Hutchinson explains, to leap from birds to mammals, the virus has had to acquire adaptations that are “finely tuned to the specifics of each species”.

This includes “getting better at copying its genome within host cells”, the virologist notes, adding that “we can see mutations associated with that occurring with this virus”.

Once a virus gains access to a host cell, it generates abundant copies of its genome, and, through packaging these copies, a virus continues to infect new hosts. The move to cows is particularly concerning as bovine are far more closely related to us than birds.

In 2009, scientists sequenced the genome of cows and found domesticated cattle share about 80 per cent of their genes with humans.

If the virus’ genome can be fully sequenced this might give more useful information, as we could see whether the virus had begun mutating to get better at spreading in humans, or if it still looked very like a cow (or bird) virus, notes Doctor Hutchinson.

The genetic sequencing of the virus from the human case clearly shows that it is a close relative of the H5N1 influenza viruses currently spreading in cattle in the USA, making it very likely that this infection originated (directly or indirectly) from the cattle outbreak.

LATEST HEALTH DEVELOPMENTS

The spillover from cows to humans already suggests that HN51 is rapidly evolving

Getty Images

Cold comfort?

Even if the latest case is traced back to cows, this is still a cause for concern.

Influenza accumulates mutations very quickly, and one of the mutations present in this virus – A156T – has changed enough that H5N1 vaccines could be less effective against it.

Research by Professor Jesse Bloom at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Washington state and his colleagues suggested this mutation can diminish the ability of antibodies to recognise and neutralise the virus.

As he explains, this has implications for vaccine development. Both the CDC and the World Health Organization have been creating weakened versions of H5N1 that can be used to manufacture vaccines if a wider outbreak ever occurs in humans.

Professor Bloom and his team have shown A156t causes a 10-to-100-fold drop in the neutralisation ability of antibodies from ferrets treated with vaccine candidates.

This would mean that vaccines designed with strains that carry this mutation won’t be viable – only one potential vaccine strain has remained effective.

He noted that the mutation underscores the challenges of the candidate vaccine virus approach, adding that the CDC’s update acknowledges the potential implication.

In practice, none of this may turn out to be a problem – most human influenza viruses cause severe disease only in a small proportion of cases, says Doctor Hutchinson.

However, much like Covid, influenza viruses can infect enough people that the “severe cases stack up”, he warns.

For now, it would seem the human cases are isolated but this is a “fast-moving situation” and it “demonstrates influenza’s capability for rapidly getting around our defences and highlights the need for this outbreak to be monitored as closely as possible”, Doctor Hutchinson adds.