Refresh

Feels like home

Nintendo isn’t doing anything new with the homescreen, but everything has seen an extra polish. Game icons are softened with round corners, compared to the harsher squares of the original, and the circular lighting around each selected icon blooms with a more vibrant purple color.

No, there’s no themes here – I was half hoping for a launch day surprise from Nintendo in that department. For now, we’re stuck with plain backgrounds only.

There’s also a new icon at the bottom for GameChat, as well as the Virtual Game Cards and GameShare buttons now available on the original Nintendo Switch as well.

This is a fairly similar experience to the previous device, though. The only difference I’ve noted so far is that individual clicks sound a little deeper and the tone changes when moving between the three horizontal menus now rise in a far more satisfying manner.

Let’s boot it up

I’ve docked the handheld and we’re off to the races with first time setup.

The whole process takes about two minutes, and you’ll need to undock the device just after you start. However, it’s pretty painless.

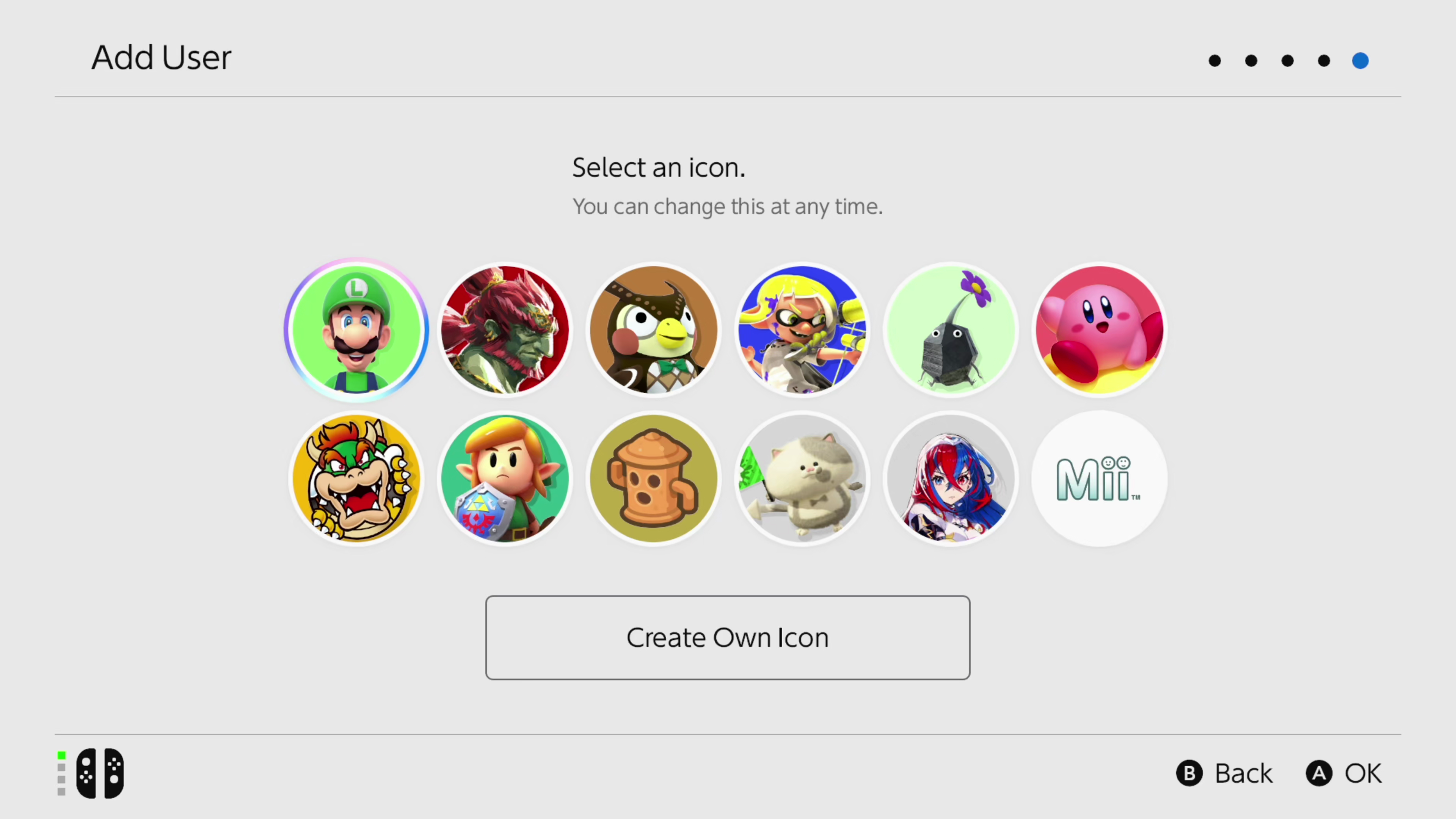

First we get a lesson on controllers and the different attachment styles, then it’s straight into choosing an icon and setting a name. Zip through any additional accounts you want to add, have a gander at parental controls and finally we’re treated to a jolly little jingle and a zippy Switch 2 animation.

Now I’m at a blank, but very recognizable home screen.

Thumbsticks

The original Joy-Con thumbsticks have never been my favorite, but the Switch 2 iteration is tighter, smoother, and significantly larger. The biggest difference I’m feeling between the two right now is right at the edge of that extension. I can feel the original gamepad’s individual notches around the outer edge of the stick itself, whereas everything’s buttery smooth here.

That’s going to make for far more comfortable movement overall, everything feels almost cushioned by comparison.

This is still a rubber topper, but it’s got much larger bumpers around the edge and a softer feel overall. I’ve only jiggled it around so far, but I can already feel slightly more purchase with my thumb, which could hopefully clear up some of those precision issues I’ve been slamming Ninty for over the years.

First impressions

This is a serious brick of a device, weighing a lot more than I remember from my preview days. It’s just as slick in the hands, though, with a fantastically cool matte finish and a real heft behind its form factor. That’s all while feeling like a slimmer device than the Switch OLED (it’s not actually, it’s just a lot better looking).

Having it in my own space now, it’s only just occurring to me that the soft-touch finish could be more prone to scratches than before. It feels like the kind of plastic that will quickly show those smaller surface nicks and bruises, though I’ll have to fully field test before I can say for sure.

It definitely feels like a more expensive device than the original Switch OLED, and I’m surprised how good the controls feel in my hands this time around as well.

I’ve just noticed something while putting the Joy-Con on the Nintendo Switch 2 for the first time

You can connect them backwards and upside down.

That’s an odd decision, I can’t believe there’s any real gameplay benefits to playing with your controller upside down – and it could lead to more frustration than it’s worth in the longer run. Sure, you’ll always see which way up your screen is – but I haven’t switched this bad boy on yet. I only knew from the hinge placement.

I’m definitely checking whether they actually work in different orientations once we get this thing up and running.

Onto the main event

I’ve torn open that box and everything’s here, huzzah!

It’s a slick unboxing experience for those who cherish these initial moments with their consoles. First up you’ll find those all-important Joy-Con, with the tablet nestled neatly underneath. Then we get into the dock. Video Producer Hal Dimond says it gives “big wireless router energy”, and I’m not disputing that. It’s much chunkier than the original and the plastic chassis doesn’t help dispel its modem vibes.

These back buttons feel slick

I’ve opened up the Switch 2 Pro Controller so far and immediately noticed something I didn’t quite appreciate during my preview time. These back buttons feel amazing.

They’re a little softer and lighter than I’m used to, but there’s still a satisfying clack to each press. Moving the thumbsticks around in-hand, there could be some threat of accidental presses due to that shorter stop, but overall I’m a fan of this feel initially.

Here we go!

It’s been a long old wait, but we’re breaking into the Nintendo Switch 2 box right now – stay tuned as we get all the bits and pieces out for the first time. I’m expecting things will look fairly similar to the original releases – the box looks to be about the same size as the Nintendo Switch OLED was when all packaged up. We already know there’s a dock, Joy-Con grip, cables, controllers, and the tablet itself inside the box, now we’ve got to get them out in person.